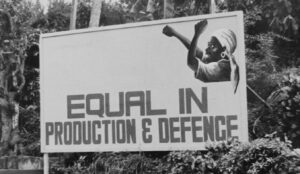

Women’s participation was very important for the overthrow of the dictatorial regime of Eric Gairy. The St Georges Progressive Women’s Association (PWA), set up in 1977, was very active prior to 1979, campaigning for better wages, employment for women, better housing, medical facilities and democratic rights and, of course, opposing the “jobs for sex” that was a part of the endemic corruption under Gairy.

The PWA had its first post-Revolution meeting in June 1979 but it was realised that a different form of organisation was needed to construct the new society from that required to overthrow a dictatorship. It is one thing to outlaw the demands by employers and civil servants for “sexual favours” in return for employment, but the problem could only really be solved when the 70 per cent unemployment rate that women suffered under the old regime is massively reduced by developing the economy. Grenadian women could only achieve real equality as part of the overall development process that the Revolution aspired to build.

National Women’s Organisation

The PWA gave way to the National Women’s Organisation (NWO), which held its founding general meeting in December 1980 although it already had 1,500 members in 47 groups. By December 1982, at the NWO Congress, it had 6,500 members, 22 per cent of the female adult population of 30,000. The NWO was at pains to stress that it was open to all women. It saw its role as a mixture of encouraging popular participation, promoting government programmes and holding government departments to account. Its founding statement said:

The N.W.O. is not for some women only, it’s for all women. It joins young and older sisters together. Our members are road workers, nutmeg pool workers, housewives, students, agricultural workers, unemployed sisters, teachers, nurses and domestic servants. You don’t have to support any political party or any particular church. You don’t have to join the militia though many N.W.O. members do. The N.W.O. is for all women who support the Revolution, defend equal rights and opportunities for women and want to see Grenada progress and move forward…

The NWO was also the main pressure group for women’s rights and equality. The organisation’s 1981 plan, for instance stressed the objective of ensuring the functioning of the free milk programme, neighbourhood clean-up and house repair programmes as well as monitoring government programmes for primary health care, free school meals, books and uniforms.

Education

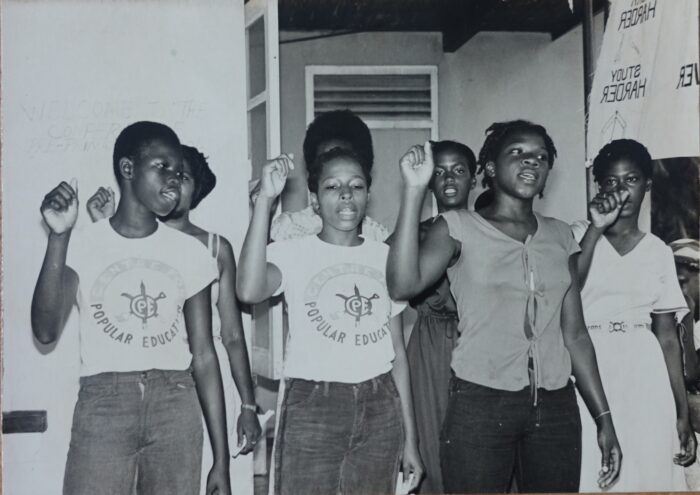

In the field of education, the 1982 NWO congress made women’s education a priority, in particular encouraging full participation in the Centre for Popular Education. The NWO collaborated with the Ministry of Education in developing the curriculum of mass education for women, which included:

• The law of equal pay

• Child care provision

• Maternity leave.

• Grenada’s history from the Caribs to 1979

• The economy

• Overcoming underdevelopment

• World history and international affairs

• Women’s involvement in People’s Power

• Maternity law

• First aid.

The NWO also led the other mass organisations in establishing, servicing and running the day-care centres in order to enable more women to enter the workforce. This was part of women’s involvement in “voluntary community work” such as road repair, in which many women moved out of their traditional roles into heavier manual labour. There was considerable effort to encourage women and girls to go into what had previously been seen as “male occupations” with laws stipulating equal pay for men and women in the same job. There was however, little effort made to persuade men and boys to enter traditional “female” occupations.

Merle Hodge, coordinator of the Curriculum Development Programme, wrote in the Free West Indian in 1980:

The new woman of Grenada will be the product of a changing education system which is geared towards equal educational exposure for girls and boys and a more conscious attack, through education on the roots of sexual stereotyping than is evident anywhere in the English-Speaking Caribbean.

Inequality

Inequality

The Revolution had to address the issue of inequality of women in society and sought to do so by introducing new laws. One of the major problems is not only inequality in the eyes of the law, which is easily changed, but also an ideological struggle, accompanied by organisation and political action, to overturn the traditional attitude to women’s role in society. Nevertheless, legal changes to facilitate women’s greater involvement in the economy do provide a framework within which this ideological struggle can take place.

The law on equal pay was thus an important measure to promote equality, but needed proper childcare arrangements to enable women’s entry into production. So a great deal of emphasis was put on the day-care facilities. The other mass organisations were involved in this work at local level, with the youth organisation, people’s militia and trade unions working together to establish, furnish and run the centres. Another important measure to facilitate women’s employment was the Maternity Leave Law, which entitled women who had worked for more than eighteen months for the same employer to three months of maternity leave, with full pay for two months. It also guaranteed women the right to re-employment with the same employer after three months. It is significant that pressure from the NWO considerably improved the provisions and they were instrumental in pushing for the first prosecution of an employer who refused to comply.

Activism

But women were also in the forefront of political activism – the fact that, in the June 1980 terrorist bomb attack on a political rally, the three persons killed and the majority of the injured were women, is evidence that women were present in large numbers.

After this outrage, the majority of new recruits to the militia were young women and if anything women’s organisation and determination were strengthened, as voiced by 60-year-old Agatha Francis, who was interviewed by Chris Searle: –

“… and for the women, they are proud and boast up of Maternity Leave. The kind of bad treatment the men give the women before, they done with that. The Revolution bring we love, and is that love that teach the men different, bring them work and cause them to respect we.”

Women and The Grenada Revolution

The majority of publications on the Grenada Revolution have been written from the male perspective. With Comrade Sister: Caribbean Feminist Revisions of the Grenada Revolution we get a distant, and hopefully objective, female perspective of how the Revo’ supported women and, some would say, did not go far enough.

Following the recent launch of Comrade Sister: Caribbean Feminist Revisions of the Grenada Revolution, Laurie R. Lambert, an interdisciplinary scholar working at the intersection of literature and history in African Diaspora Studies, expands on the content of her publication.

Comrade Sister, University of Virginia Press 2020, examines the gendered implications of political trauma in literature on Grenada. The book analyses how Caribbean women writers use authorship as a means of expressing cultural sovereignty and critiquing the inadequacy of hierarchical, patriarchal, and linear histories of a black radical tradition as they narrate the Grenada Revolution. In so doing, Lambert reads Caribbean literature as a primary site for the excavation of gendered readings of revolution, identifying the marginalized voices of women and girls at multiple unexpected sites of political formation.

In 1979, the New Jewel Movement under Maurice Bishop overthrew the government of Grenada, establishing the People’s Revolutionary Government. The United States under President Reagan infamously invaded Grenada in 1983, staying until the New National Party won election, effectively dealing a death blow to socialism in Grenada.

With Comrade Sister, Laurie Lambert offers the first comprehensive study of how gender and sexuality produced different narratives of the Grenada Revolution. Reimagining this period with women at its centre, Laurie Lambert shows how the revolution must be recognized for its both productive and corrosive tendencies.

Quite rightly Lambert argues that the literature of the Grenada Revolution exposes how the more harmful aspects of revolution are visited on, and are therefore more apparent to, women. Calling attention to the mark of black feminism on the literary output of Caribbean writers of this period, Lambert addresses the gap between women’s active participation in the Caribbean revolution versus the lack of recognition they continue to receive.

To subscribe to Grenada-Forward Ever’s email list. Go to https://mailchi.mp/65d89750ca33/so0jveueff or https://bit.ly/3hJNmBL.

To supply the names and dates of women, men and events significant to Grenada’s place in the world please email the Secretary of Grenada – Forward Ever at the email address below.

We welcome any corrections, additions and amendments to our articles, posts and calendar entries. To do so please contact the Secretary of Grenada – Forward Ever at mob’ +44 7401 625 276 or email: info@grenada-forwardever.net.